Time to say goodbye to the two-state solution. Here’s the alternative

Time to say goodbye to the two-state solution. Here’s the alternative

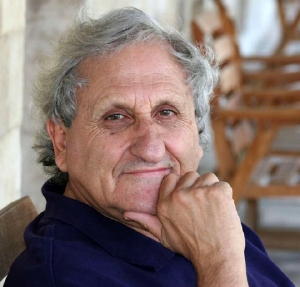

A.B. Yehoshua, one of Israel’s staunchest fighters for the two-state solution, lays out a proposal for an Israeli-Palestinian partnership

A.B. Yehoshua | Apr. 19, 2018 | 2:59 AM | 33

On the third day of the Six-Day War, when the conquest of East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip had been accomplished, I remember myself saying in a celebratory tone, “Now a state has to be established for the residents of the territories.”

Initially, it was customary to say “residents of the territories,” not “Palestinians,” and the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were called “territories,” which gradually morphed into “administered territories,” and in the past 20 years into “occupied territories.” The peace camp slowly introduced the term “Palestinians,” in place of “Land of Israel Arabs,” into the public dialogue. The national camp, as it’s known, which attached the adjective “liberated” to the territories, gradually insinuated the names “Judea and Samaria” into the national discourse, as natural and legitimate parts of Israel itself, like East Jerusalem, which joined the western section, creating one city.

In this piece, I will try to avoid the terms “left” and “right,” using instead “peace camp” and “national camp.” Some left-leaning people, driven by a concern for social justice, have always been active in the “national camp,” while many “peace camp” activists espouse a liberal capitalist approach that is completely at odds with left-wing ideology. Still, beyond the mutual insults in the polemics, it’s widely agreed that the majority of those who identify with the “peace camp” are driven also by saliently national motivations, and on the other hand, some in the “national camp” seek equitable coexistence, according to their lights, with the Palestinians.

That said, it’s noteworthy that in recent years, despite the virulent tones and the heated, personal language used by both sides, the truly substantive arguments about the “two-state solution” are becoming more acerbic – because of the chaotic situation in the Middle East, the lessons of the unilateral withdrawal from Gaza, the passivity of the Palestinian Authority and the despair of the Israeli peace camp, which has begun to devote energy to other civil struggles.

But above all, the two-state solution is fading because of the constantly expanding settlements in Judea and Samaria. Indeed, according to many experts who are familiar with the demographic and geographic reality, it is no longer possible to divide the Land of Israel into two separate sovereign states. Similarly, the possible partition of Jerusalem into two separate capitals with an international border between them is becoming increasingly untenable.

For 50 years – during most of my adult life – I worked tirelessly for the two-state solution. In the mid-1970s, I added my voice to those recognizing the Palestine Liberation Organization as the representative of the Palestinian people for negotiations, and I was a signatory to the Geneva Agreement in the early 2000s. Together with most of the nation, I supported Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, and during the various intifadas and the expansion of the settlements, I never stopped putting forward possible ideas for the border crossings and the status of Israeli minorities in the future Palestinian state, in an effort to give life to the receding two-state vision.

In the face of countless frustrations, generated by both the Israeli government and the PA, I too, along with the entire peace camp, hoped that the international community, and particularly the United States and Europe, would exert economic and diplomatic pressure on both sides so as to force them to find the way to a historic compromise to one of the most persistent and complex disputes in the world since the start of the 20th century.

And in fact, the anticipated moment ostensibly arrived when the official Palestinian leadership, and also two right-wing prime ministers – Ehud Olmert and Benjamin Netanyahu – formally announced their desire to work for the two-state solution. Before his resignation, in 2009, Olmert initiated a detailed and extremely generous plan for dividing the Land of Israel into two states. However, according to Olmert, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas evaded most of the meetings that were intended to discuss the plan. As for Netanyahu, there’s no knowing what he was actually thinking in his occasional references to the two-state idea.

Yes, there are people in the right-wing parties who stammer “two states” – among them a few in Likud, Yisrael Beiteinu, Kulanu and even Shas (the ultra-Orthodox Ashkenazi parties don’t deal with such petty matters). And, of course, the two-state principle is posited at the center of the political solution proposed by parties such as Yesh Atid, Zionist Union and certainly Meretz and the Joint List of Arab parties. The PA and most of the moderate Arab states also advocate the two-state solution, which is also the official position of the majority of the international community.

A solution to the conflict in the form of the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel – which seemed fantastical and unrealistic 50 years ago – has thus become the cornerstone of the entire political arena. In the 1970s, Prime Minister Golda Meir ridiculed the term “Palestinian” as both a political and identity concept, claiming with irony that she, too, was actually an authentic Palestinian. (Indeed, with her self-righteousness, stubbornness and shortsightedness, she resembled many Palestinian leaders.) Today, though, right-wing prime ministers employ the term naturally and meet openly with PLO representatives.

Yet, just when the term “Palestinian state” is becoming a staple fixture in the international sphere, I and some of my good friends who fought for it for 50 years feel – and I hope I am proved wrong – that this vision is no longer viable in practice. Indeed, it has become only a deceptive and crafty cover for a slow but ever-deepening slide into a condition of vicious occupation and legal and social apartheid with which we in the peace camp – Israelis and Palestinians alike – have come to terms out of weariness and fatalism.

Accordingly, we must try to examine the situation with intellectual honesty and think about other solutions that can stop this process and reverse it. What’s in danger now is not Israel’s Jewish and Zionist identity but its humanity – and the humanity of the Palestinians who are under our rule.

Lengthy and stubborn

If we date the genesis of Zionism to the end of the 19th century, and if the first new Jewish settlements in Palestine were being built by the Lovers of Zion movement as early as in the 1870s and 1880s, this means the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is almost 150 years old. One’s amazement at the length and obduracy of the conflict is only heightened by the fact that it is one of the best known and most deliberated conflicts in the world, especially during the past 50 years. High-ranking envoys come and go, and presidents, foreign ministers and prime ministers in both the present and past have tried to resolve it. In 2000, U.S. President Bill Clinton set aside everything else to spend days discussing the intricacies of the border between a future Palestinian state and Israel. John Kerry noted that more than 60 percent of his foreign trips as Barack Obama’s secretary of state were aimed at resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The conflict is a regular subject at the United Nations and in many other international organizations. The current American president speaks of Israeli-Palestinian peace as a “deal.” It’ll be a long time before that “deal” is cut, but in the meantime a great many people have made handsome “deals” out of this conflict.

The deep reason for this state of affairs is, I believe, the singularity of this conflict. To the best of my knowledge, there is no other example in human history of a nation that abandoned its land at least 2,000 years earlier and wandered across the globe, and then, after millennia, sought (as it became the target of intensifying hostility) to return to that historic homeland, with which it maintained a spiritual and religious connection but to which it had stubbornly avoided returning for centuries. Thus, at the beginning of the 19th century, only 10,000 of the world’s 2.5 million Jews lived in Palestine (there were 40,000 Jews in Afghanistan, 80,000 in Yemen and already a million in Poland). A hundred years later, at the time of the 1917 Balfour Declaration, even with the momentum of Zionism, there were 550,000 Palestinians in Palestine but only 50,000 Jews out of a worldwide population of almost 14.5 million (data from the Encyclopedia Hebraica).

But it’s not only the late and amazing return to Zion – which we take pride in and which the Palestinians and the Arabs reject – but the fact that the two peoples are effectively claiming sovereignty over the same territory. It’s not only a dispute over a particular region, of the kind history is familiar with; at bottom, this is a dispute over full ownership. That the Palestinians rejected the Balfour Declaration is perfectly understandable, and not only because Britain did not possess the moral authority to promise Palestine to the Jews. By the same token, the League of Nations and its successor, the United Nations, lacked moral or legal authority to divide a country between its inhabitants and a people coming from the outside.

Both the Palestinians and the Jews rebelled against the British presence in Palestine in the 1930s and ‘40s. For this land does not belong to Britain but to its inhabitants, both Jews and Palestinians asserted, in accordance with the universal moral imperative by which a land belongs to its occupants and not to the army that conquers it.

But the conflict also grew fiercer because of the demographic relations between the two peoples, which even today continue to rule out compromise and partition. The Palestinians rightfully rejected compromise and a partition with the Jews in both 1917 and 1947. In 1917, if only a quarter of the world’s Jewish population – meaning around 4 million Jews – had come to Palestine, the Palestinians would not have had a square centimeter on which to hoist their flag. By 1947, there were 1.3 million Palestinians and 600,000 Jews in the country, but once more, some 12 million Jews were elsewhere, some of them homeless Holocaust refugees, others distraught by the intensity and cruelty of the hostility they had endured in the war. Thus the Palestinians’ opposition to the UN resolution was clear and natural, as it demanded that they turn over half of their homeland to a people that had resided in it 2,000 years earlier but that since then had been scattered across the globe.

Indeed, in 1948, the Palestinians had every chance, with the aid of seven Arab states, to crush the small, nascent, objectively weak Jewish community. The deputy chief of staff of the army at the time, Yigael Yadin, told the Jewish community’s leadership that Israel had a barely 50 percent prospect of surviving what evolved into the War of Independence.

Yet even if the roots of this distinctive conflict are understood, we still need to ask why it is that after 70 years of Israeli independence, and particularly after the vanquishing of the Palestinians and the Arab states – both in the War of Independence, the wars of 1967 and 1973 and in the second intifada – it remains impossible to conclude this conflict in the way that the entire world is suggesting: by partition and compromise.

Double defect

Homeland is the first and most important element in every national identity, whose other components are built on its foundation: language, religion, history, culture and in some cases common origin. Religion and language can be shared by a number of peoples, but it’s territory that creates the distinctive basis of nationality.

Seeking to understand the reasons for the depth and obduracy of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, we discover that it is the defective character of both the Jewish and the Palestinian national identities that is causing the conflict’s exacerbation. And not least, because the defects are mutual opposites. Before proceeding, I must point out, in all fairness, that the singular defect in the homeland element of the Jewish people’s national identity is far more serious and disaster-ridden than the comparable defect in the Palestinians’ homeland component.

From the dawn of the Jewish people’s emergence – and it is immaterial whether it actually took place this way historically or is only a mythological-religious foundation that was embedded deep in the national consciousness – the homeland component of the Jewish-Israeli national identity has lost its primary and key role to the religious-divine component. Certain facts can be enumerated in the deliberate process of weakening the homeland element in the Jewish-Israeli identity. Abraham, the first Hebrew, was enjoined to leave his father’s house and his homeland and go to a new land, which was defined as a holy land, a designated land given to him in a covenant by God. Thus it was not akin to a homeland that was granted to the Jewish people naturally, as with every other people.

According to the biblical myth – the formative myth in the Jewish national consciousness, both religious and secular – the Israeli-Jewish national identity was not generated and did not spring up naturally in its homeland, the Land of Israel, but in Egyptian exile.

Likewise the Torah, as a primary element of the national identity, was not given in the homeland, in the Land of Israel, but in the Sinai desert, which is no one’s homeland. Hence, the promised territory, which is meant to be a natural foundation for the nationhood of the people that came out of Egypt, was not bestowed to it thanks to conquest or natural growth, but only by dint of loyalty to God’s laws.

Abandonment or violation of those laws will bring calamities on the people, of which the most egregious will be their expulsion from the Land of Israel and their dispersal among the nations.

However, because homeland as such is only a secondary component in Jewish identity, its loss need not erase and annul the national identity. The nation that was born in exile will return to exile and continue to exist there. The homeland, the territory, is conditional, and only God is the ultimate decider. There is no other people in the world that, after losing – more precisely, abandoning – its homeland and dispersing for many centuries to foreign territories across the world, succeeded, or at least part of it did so, in preserving its national identity.

Exile is an immanent and legitimate part of Jewish identity. For almost 2,000 years, the vast majority of the Jewish people did not live in the “homeland” given it by God but in the homelands of other peoples. The ratio between the number of Jews who preferred of their own volition to live outside the Land of Israel and those who lived there until Israel’s establishment is astounding and shocking. For centuries, as much as Jews around the world vowed to seek redemption and return to the Land of Israel, and reiterated the verse “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem” – the Jewish presence in the Land of Israel was minuscule, if not negligible.

The Jews’ obdurate avoidance of settling in the Land of Israel is especially blatant among the Jews of the East in the 400 years in which Palestine was under Ottoman rule. Numerous Jewish communities thrived across the vast Ottoman Empire, from which many could easily have settled in the Land of Israel. But the Eastern Jews who moved about between the many communities did not go there. In 1839, according to the records of the British consul in Palestine, there were only 10,000 Jews in the country, among them Ashkenazim from Eastern Europe.

The Jews’ tendency to recoil from their true historic and religious homeland was indicative of a disastrous flaw in their identity. Because the homeland element is essentially secondary in the Jews’ national consciousness, they also project this feeling on others, and as such diminish the identity value of homeland in other peoples. They don’t understand that each case of their dwelling among other peoples constitutes a deep, danger-fraught infiltration into an identity that does not belong to them. Resorting to an image, we can say that the majority of the Jews treated and continue to treat the homelands of other people like a hotel chain, and so, together with the “Jewish bookshelf,” move from hotel to hotel according to the changing conditions of accommodation. “The Jew [is] everywhere and nowhere,” Hannah Arendt observed of Jewish existence, and in her private life also manifested that assertion.

Even though the Jews tried throughout history to behave like good, polite customers in these “hotels,” their very presence fomented harsh reactions. These took the form of expulsions, bans on their entry and attempts to change their identity by making them convert or even effectively imprisoning them – that is, by preventing them from leaving the “hotel” when conditions changed there, as was the case, for example in the Soviet Union and in Syria. As a result, the wandering between places of exile also brought about a dramatic reduction in the number of Jews. From a population of up to 4 million at the end of the Second Temple period, their number had declined to 1 million by the beginning of the 18th century.

The most horrific reaction, however, was annihilation, and precisely in places where the Jews’ infiltration into the local national identity was extremely deep. From this perspective, the Holocaust was the hardest and cruelest catastrophe endured by any people in human history. In the course of five years, a third of the Jewish people was destroyed – not over territory, not because of their religion and faith, not for their material possessions and also not because of some ideology they espoused uniquely. That terrible debacle, which some of the fathers of Zionism foresaw (“If you do not liquidate the Diaspora, the Diaspora will liquidate you,” the founder of Revisionist Zionism, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, wrote), was caused not only by the unimportance of territory as the primary, firm basis in their national identity, but also because of insufficient recognition by them of its importance in the identity of other peoples.

Double barrier

Parallel to the Jews’ historic disdain for territory as the primary basis of national identity, both of themselves and hence of other peoples as well, we find an opposite Palestinian flaw. For the Palestinian, the house, or the village, and not the entire territory of Palestine, symbolizes the primary and principal basis for his identity. The result is that the clash between these two flaws actually aggravates and sustains the conflict between the two peoples.

I cannot pretend to be highly knowledgeable about the intricacies of Palestinian nationalism. Still, a perusal of its emergence turns up a process that began during the long rule of the Ottoman Empire. Because the empire was essentially Muslim, and the Arabs within it belonged in their perception to one nation that spoke a single language (despite the richness of its different dialects), naturally it could not develop and consolidate a singular territorial nationality within clear and defined borders. But after the empire disintegrated, in the wake of its defeat in World War I, and consolidated into more clearly defined ethnic borders, the Arab states gradually began to coalesce in the Middle East, under the patronage and with the encouragement of the colonial powers Britain and France. In this way, the national identities of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, the Hashemite Kingdom, Saudi Arabia and Yemen began to develop.

But in Palestine the development of the Palestinian nationality remained stuck in the face of a double barrier, namely, Britain’s military and administrative rule, which was supposed to guarantee the implementation of the mandate of the Balfour Declaration, and the increasing arrival of Jews.

Instead of an autonomous national administration, like those the Iraqis, Syrians and Lebanese gradually began to develop when they gained independent states, the Palestinians remained at a level of extremely limited self-rule, which was managed within a framework of clans and village dignitaries, without concrete power of enforcement. The political leadership, too, headed by the Higher Arab Committee under the grand mufti, lacked truer legitimacy among the Palestinians, besides which the population also included Christian Palestinians and Druze.

Of course, if the central national government is feeble and limited, and lacks a tradition of concrete national authority, as existed in the past, the smaller units – villages and families – become the focal points of national identity. The national consciousness that expresses itself in a sense of belonging to the whole homeland is diminished and weakened. The situation was further compounded after 1948, when the Palestinian nation was split among five countries at least: Israel, Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon and Syria.

Following the British departure, the village-clan structure was one of the factors that led to the Palestinians’ failure in their war against the Jews, who were fighting for their lives with their back to the sea. The Palestinians’ basic loyalty was to village and home, not to homeland in the broad sense. Even though the Palestinians outnumbered the Jews two to one and were bolstered by military aid from Arab countries, not only were they unable to eradicate the fledgling Jewish state, they also ended up losing part of their allotted territory under the UN partition plan.

In his excellent new book “The Battle on the Qastel: 24 Hours that Changed the Course of the 1948 War between Palestinians and Israelis” (in Hebrew), veteran journalist Danny Rubinstein describes an illuminating episode that gives vivid expression to the connection to village and home that overrides the national interest. During an attack by the Palmach, the Jewish shock troops – an operation that went partly wrong – Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini, the legendary, revered Palestinian commander, lost his way between positions, and was killed by Jewish troops. Not realizing whom they had killed, they left Husseini’s body where it lay. The Palestinians, thinking he had only been wounded and taken prisoner by the Israelis, summoned help from the local villages to rescue him. A thousand fighters responded immediately to the call and recaptured the village of Qastel and its fortress, inflicting severe casualties on the Jewish forces.

Hussein’s body was found and taken to Jerusalem for a magnificent burial. The Palestinian fighters who remained in the newly liberated village were ordered not to leave Qastel until new troops had arrived to replace them. However, the Arab villagers, who with great effort captured the strategic outpost that was to determine the fate of the siege of Jerusalem, ignored the order and within a few hours returned to their villages and homes, just a few kilometers from the site of the battle. Effectively, they handed over Qastel to their enemies without a fight. Their loyalty and attachment to their villages trumped their overall national identity.

To this day, Rubinstein writes, 70 years after the 1948 war, the Palestinians define themselves in the alleys of the refugee camps according to their villages of origin, which remain the heart of their identity. Yet the Palestinians who inhabit the refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza Strip are not actually refugees, but only displaced persons still living in their homeland. Whereas the Israelis – who were in any case relatively small in number – who in the 1948 war were forced by the Palestinians to leave their homes in the Etzion Bloc, Atarot, Neveh Yaakov, Beit Ha’arava and the Old City of Jerusalem never considered themselves refugees, only displaced persons who remained in the homeland, and they immediately integrated into other locales. Even the Palestinians who left or were expelled from Palestine to Lebanon, Jordan, Syria or Egypt in 1948 could have theoretically returned to the areas of the homeland that were ruled for the next 19 years by Jordan and Egypt. It wasn’t until after the 1967 war, when Israel closed the borders to them definitively, that they became true refugees.

The insistence on seeing one’s home or village as the primary and almost exclusive source of national identity – through the refugee’s “personal right” to return to his original home – exacerbates and sustains the conflict. On top of which, the United Nations, through its UNRWA relief agency (perhaps because of repressed guilt at the partition plan), granted refugee status to the Palestinian refugees’ offspring, too, even today, to members of the fifth generation. Yes, a Palestinian has the right to long for the moment of Israel’s destruction, when he will be able to return to his village or to the home of his forefathers, just as the displaced (not refugee) settlers from Gush Katif in the Gaza Strip can dream of the moment when that area will be reconquered and they can rebuild their homes, which were demolished by the Israel Defense Forces in 2005. But the question must be asked: What happens in the meantime?

The fact that refugees have lived for 70 years in miserable, difficult camps in Gaza, which is after all part of the Palestinian homeland, and insist on condemning themselves to a shameful life of refugeehood within 10 or 20 kilometers of their original homes in Ashdod or Ashkelon, from which they fled or were expelled, transforms the rusting keys of their lost homes into basic symbols of Palestinian nationhood, which for its part needs to confront Jewish nationhood. The latter people, in the meantime, after 2,000 years of drifting around the world, was seized by biblical longing, and, not satisfied with controlling the 78 percent of Palestine that was recognized as the State of Israel after the War of Independence, also needed to gnaw away at the remaining 22 percent – the West Bank and the Gaza Strip – that had remained in Palestinian hands.

The combination of these two substantive defects – expressed through the degrading penetration of the Palestinian identity through the settlements established in the territories, counterpoised to the sacred Palestinian principle of the return of the refugees to their homes within Israel proper – is what makes compromise and conciliation so difficult to achieve. The cruelty and absurdity of both sides are well illustrated in the Israeli settlement project in the Gaza Strip, which ended – and not by chance – with a total Israeli defeat on the one hand, and with an absurd and destructive response of the defeated, who instead of building and rehabilitating Gaza following its liberation from the cruel occupation, started to fire missiles and dig tunnels.

Reverse demography

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat noted in his memoirs that he arrived at the decision to launch the 1973 war when Israel started to settle civilians in Sinai, in the area known as the Rafah salient or the Yamit district, which was meant to act as a kind of civilian buffer (totally untenable) between Sinai and the Gaza Strip. Given that the expropriation of conquered territory for the purpose of settling foreign citizens is the deepest possible infringement of national sovereignty, it’s clear that the only legitimate response to this can be war. The decision to establish the Rafah salient was made in 1972 by the Labor Party secretariat, in what’s known as the “Galili document” (drawn up by cabinet minister Israel Galili), which was approved unanimously by ministers, MKs and others, some of them ardent socialists who were members of kibbutzim and moshavim. Ten years later, Defense Minister Ariel Sharon carried out the evacuation and demolition of Yamit for the sake of the peace agreement with Egypt, which was signed with the Likud government.

It’s true that in 1977, when Labor transferred power to Likud, there were only 3,000 settlers in the West Bank, in contrast to the nearly 400,000 Israelis who now live in the settlements of Judea and Samaria. Still, it was Labor that imparted the moral and political legitimacy to the settlements, though that legitimacy was accompanied by a sly principle of “settlement only in areas not dense with Arabs.” That principle was easy enough to implement in the Rafah salient because the 10,000 Bedouin who had lived there were forcibly evicted from their homes, their crops uprooted and their fields transformed into construction sites for the new Israeli settlements – which were thereby not established in an area “dense with Arabs.”

But in the Gaza Strip, where the Gush Katif settlements were built (also by a decision of the Labor Party), it was more difficult to maintain the sanctimonious principle of settlement in places not “dense with Arabs.” Accordingly, when Likud, and particularly its active religious-Zionist wing, came to power, the principle of the prohibition of settlements in such locations was dropped. After all, the Gush Emunim movement noted, for 2,000 years Jews had lived in places that were “dense with goyim” without losing their Jewishness. Then why, in the Land of Israel of all places, would they shun such places when the IDF was safeguarding and protecting them from the “denseness”? The trouble was that the “denseness” only intensified.

The demographic balance of forces that existed between the two peoples at the time of the Balfour Declaration – half-a-million Palestinians in the face of the almost 15-million-strong Jewish people – slowly began to change. This was due not only to the Holocaust, which annihilated one-third of the world’s Jews, but also to natural growth, and to the benefits derived by the Palestinians by virtue of their shared life with the Israelis. What still seemed natural and possible (though not moral) about realizing the concept of Greater Israel in 1967 was increasingly difficult a hundred years after the Balfour Declaration and 70 years after the UN partition resolution.

The demography began to reverse itself, or more accurately to swing like a pendulum. Yasser Arafat, the Palestinians’ chaotic leader, with his deceptive and self-righteous talk of Palestine as a “secular, pluralistic and democratic state” – after the return of the refugees to their homes within Israel, of course – was seized by dread following the waves of immigration to Israel from the Soviet Union starting in the late 1980s and the multiplication of settlements in the territories. He agreed, then, to sign the Oslo Accords, which recognized Israel as a distinct state. But he began to trample the agreement through terrorist attacks, which intensified in the second intifada, besides which Israel also still hesitated about leaving the territories, and the settlements not only failed to stop expanding, but grew more deeply rooted.

The Gush Katif settlers, who waited in 2005 for soldiers to evacuate them while the laundry tumbled in the machine and the chicken roasted in the oven, taught the Jewish people a lesson for the future: how arduous and terrible it will be to try to evacuate settlements in Judea and Samaria. The evacuation of the 8,000 Gush Katif settlers cost the state about 10 billion shekels ($2.85 billion in current terms). On top of which, the Palestinians in Gaza explained to the world, via missiles and underground tunnels, that for them the evacuation of Gaza, far from being an end to occupation, did not contain even a hint of the start of separation and conciliation.

But we still have the relatively successful story of coexistence in Israel between the Jews and the Israeli Palestinians, despite all the harsh vicissitudes experienced by both sides over 70 years: the wars, the occupation after the Six-Day War, the intifadas, the military government and the land expropriations. Still, it appears that the citizenship that was forced on or granted to the Palestinians in Israel upon the conclusion of the War of Independence in 1949 created a stable, concrete base for relations between the majority and the minority in the Jewish state, with its large national and non-territorial minority of 20 percent.

Even an outside observer with a lofty sense of human morality would give both sides – Israeli Jews and Israeli Palestinians – high marks for the wisdom of coexistence they’ve developed during the state’s 70 years of existence. There’s the Palestinian-Israeli judge who sentenced a former president of Israel to a prison term, and in so doing helped establish an Israeli moral standard; the Palestinian director of the Nahariya hospital, who in that capacity helps set Israeli medical codes; the Druze commander of a combat brigade during the 2014 Gaza war; the Palestinian-Israeli ambassadors and consuls-general around the world; the Palestinian intellectuals, scientists and high-tech people, and the talented Palestinian-Israeli artists of all kinds who amazingly steer a course between the codes of the two peoples. All these people show that despite the difficulties and injustices, the Jewish majority has succeeded, vis-a-vis a fairly large population group, in maintaining cooperation and life together amid the Middle Eastern chaos. With all the grievances and allegations of both sides, and in particular on the part of the Palestinian minority, there is still a foundation that’s right for the shared fate to which we brought ourselves with the late and partial return of the Jews to their historic homeland.

Partnership, not peace

In 2016, on the first anniversary of the death of former minister and MK Yossi Sarid, his widow, Dorit, asked me to speak at a memorial event for him at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. This was a few weeks after the publication of my proposal to grant residency status to 100,000 Palestinians living in Area C, in order to reduce somewhat the malignancy of the occupation in at least 60 percent of the West Bank – namely, in the area in which all the Israeli settlements lie. A few people in the peace camp were panic-stricken by this idea, for it was inconceivable that a veteran of that camp should put forward a suggestion whose hidden implications could be interpreted as a prelude to Israeli annexation of Area C. The principle of two states within the post-1967 borders is sacrosanct to the peace camp, and anyone who engages in heretical reflections is taking his dovish life in his hands. Nevertheless, in my remarks to a hall packed with activists – whose camp I have belonged to since 1967 – I called for an attempt to be made to examine other modes of thought as well. It is in fact becoming clear to many who are well informed about both the situation on the ground and the official contacts with the Palestinian governing authorities that separation into two sovereign states is becoming increasingly difficult and complicated. Indeed, some already view the idea as little more than an illusion designed to quell the conscience, while making do with plays, films and novels about the Israeli-Palestinian problem.

The fact is that recently, ideas have been raised in both the national camp and the peace camp about various sorts of federations and confederations, along with plans for “two states in one homeland” and other notions. I consider all these to be highly positive efforts amid the conceptual stagnation that has seized large segments of the Israeli public, and certainly many political circles. It’s true that wherever a new idea leads, a land mine, real or possible, will immediately go off beneath you, but the apartheid process that is striking deep roots in our life is far more dangerous, and uprooting it will soon be impossible.

As I emphasized at the start of this essay, it is not the Jewish or Zionist identity that I fear for, but something more important: our humanity and the humanity of the Palestinians in our midst. We are not Americans in Vietnam, the French in Algeria or the Soviets in Afghanistan, who one day get up and leave. We will live with the Palestinians for eternity, and every wound and bruise in relations between the two peoples will be engraved in the memory and passed on from one generation to the next.

In order not to leave things at the level of reproof alone, I will take my life in my hands and set forth a draft proposal that, though replete with countless problems and obstacles, is still a capable of being realized, in my opinion. I will stress that I am not offering a blueprint for a peace plan with the Palestinians, still less for a “historic reconciliation” or a “declaration of the termination of claims.” It’s not my intention to propose something that is impossible and is used, by both sides, as a kind of excuse to torpedo any possibility of an agreement. I am proposing lines for thought about how to stop the apartheid process in principle, and at a certain stage to reverse it. Accordingly, this is a unilateral plan intended for Israel that perhaps anticipates the possibility of a modicum of cooperation on the part of the Palestinians, who have also despaired of the two-state solution.

Therefore, instead of talking about peace or a settlement or conciliation, I suggest that we use the term “de facto partnership.” That’s a less ambitious but more practical term, and the amazing fact is that there has long been security cooperation between Israel and the Palestinians in the West Bank.

The lines of thought that follow are intended also to serve as a challenge and to encourage other initiatives, different but welcome, if they are indeed intended to fight or diminish the “cancer of the occupation,” which has long since begun metastasizing to other parts of the body politic.

First, the plan relates only to the West Bank, or Judea and Samaria. It is not intended for the Gaza Strip, which is now effectively a sovereign Palestinian territory, properly armed, administered by an independent government, and with an open passage to Egypt and from there to the world.

The plan requires an absolute halt to the building of new settlements and to the expansion of existing ones, but does not require the evacuation of any, apart from the dismantlement of unauthorized outposts, which are illegal even by Israeli law.

The eastern border of the Land of Israel/Palestine would remain under full Israeli control. The security checks at the crossing points to Jordan would continue to operate as they do today.

Residency status would be offered to all residents of the West Bank, and in its wake, within five years, also Israeli citizenship, including all the attendant rights and obligations.

Proper compensation of land or money would be arranged for private Palestinian land in the West Bank that has been expropriated by Israel since 1967.

In Jerusalem, citizenship would be offered immediately to all Palestinians already possessing residency status, which was granted in the wake of the annexation of the eastern part of the city and its surrounding villages in 1967.

The security measures and checkpoints would remain in place as needed, but in principle, free movement of Palestinians into and around Israel would be permitted, as it is permitted today to the Palestinian residents of Jerusalem and to a significant portion of the Palestinians residing in Judea and Samaria.

A sincere option, active and generous, would be proposed for the rehabilitation of the refugees, whether in new communities or by expanding existing Palestinian locales.

The holy places in the Old City of Jerusalem would be administered jointly by the three great religions.

Israel’s form of government would be changed from a parliamentary to a presidential regime. The president will be elected in a general election, similar to what exists today in the United States and other countries. The intention here is to reduce the deceptive and manipulative dependence of the executive branch on the legislative branch.

The country would be divided into districts, each of which would send two representatives to an upper legislative chamber, without connection to the size of its population (like the U.S. Senate).

The districts would be granted more autonomy in the realm of municipal laws, and of course in all matters related to education, culture and especially religion.

The electoral system for a lower chamber would be changed from proportional elections to regional elections, in order to enhance the efficacy of the districts (like the electoral system in Britain and other countries).

The security forces of the Palestinian Authority, with which reasonable cooperation now exists, would be united with those of Israel in a joint police force.

The ID card of the new Palestinian citizens would state “The Israeli Palestinian Federation,” but in terms of rights and obligations would be identical to the Israeli ID card.

The (Jewish) Law of Return would remain intact, but with more stringent examination.

The return of Palestinian refugees from outside Israel-Palestine would not be allowed, other than within a strict framework of family unification.

A request would be made to the members of the European Union and to the world’s other countries for a generous loan/grant for the welcome process of annulling apartheid and for rehabilitating the refugee camps in new cities.

The Israeli-Palestinian federation would ask to join the existing European community as an associate member bearing a special status.

Nonviolent partnership

These are all general lines of very preliminary thought, filled with tough problems and complicated to implement, and which would invite no end of opposition from both the Palestinian and the Israeli sides. But at heart, they are thoughts that grope toward the possibility of creating a nonviolent partnership between Israelis and Palestinians.

Jewish identity (however it is interpreted) existed for thousands of years as a small minority within large, powerful nations, so there is no reason for it not to exist also in an Israeli state even though it contains a Palestinian minority so large that it can be termed a binational state. Consider the fact that in 1967 there was not even one Palestinian in Jerusalem the capital of Israel, whereas now, 50 years later, 300,000 Palestinians live there. Has Jerusalem’s Jewish identity declined or grown? Many would say that the Jewish identity of Jerusalem has only increased, and certainly has not diminished.

Similarly, Israel within its pre-1967 borders is a country containing a large Palestinian minority, which possesses some distinctive merits of its own. The Palestinians have been natives of this homeland for generations, most of them also know Hebrew and are familiar with the Israeli codes and share them. It would be possible to create a reasonable partnership with them for the benefit of both sides – a human status quo that grants civil status to every person.

The proposal put forward here, and many other proposals that are now under consideration and discussion by people from across the political spectrum, raise serious problems, but there is always hope that partnerships will be able to moderate the obstacles in attempts to cope with them. Let’s not forget that all these plans are, after all, attempts to extricate ourselves from the principal moral quagmire into which we are relentlessly sinking.

At the same time, in spite of everything I’ve written here, if a political force can prove to me, in words and in deeds, that it would still be possible to achieve a separation into two states, of a sort that both sides would accept officially, I will follow it through fire and water.