Israele, Grossman: “Ormai Bibi è nella testa del Paese. La democrazia è sparita”

10 Aprile 2019

dalla nostra inviata FRANCESCA CAFERRI REPUBBLICA

TEL AVIV.

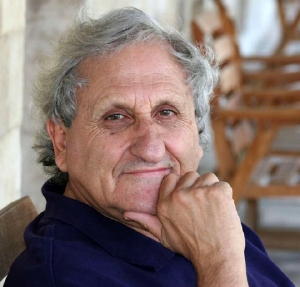

All’indomani del voto con cui Benjamin Netanyahu si è imposto ancora una volta al

centro della scena politica, David Grossman è affranto. Come la parte del Paese

a cui, da anni, insieme a un’intera generazione di intellettuali il grande

scrittore israeliano dà voce. «Ci serve solo qualcuno con un po’ di coraggio,

che dica alla gente che la pace si può fare ancora: ci giochiamo davvero

tanto», ci aveva detto poche ore prima del voto. A urne chiuse la

consapevolezza amara è quella di aver perso la sfida: e in maniera brutale.

Signor Grossman, con la vittoria in

queste elezioni Netanyahu si appresta a diventare il primo ministro più longevo

della storia di Israele. Dopo tanti anni, ha capito qual è il segreto del suo

successo?

«Bibi ha un potere sulla

gente che è molto difficile spiegare in modo razionale. È un ottimo politico,

ma il segreto non è quello: ha trovato il modo di rispondere alle paure più

irrazionali e profonde dei sionisti. L’intensità della manipolazione che ha

messo in atto sulla società israeliana negli ultimi anni è difficilmente

spiegabile per chi non ha assistito al suo sviluppo: è entrato nella testa del

Paese e tutta la vita del Paese oggi si svolge nella sua testa. E’ come se

l’intero Israele fosse soggetto alle sue priorità, alle sue ansie, alla sua

visione del mondo: e nessuna altra visione trova spazio nel dibattito. Abbiamo

accettato che facesse lui le regole del gioco, senza troppa opposizione: ed

ecco il risultato».

Non sembra sorpreso…

«Non sono sorpreso

infatti. Si sa che in Israele il blocco delle destre è più forte, anche solo

dal punto di vista demografico. Ma Gantz è un uomo di centro-destra, nonostante

abbiano tentato di etichettarlo come un estremista di sinistra: speravo che

riuscisse ad attirare più voti da destra. Invece ha solo cancellato la

sinistra, inglobando i suoi elettori».

Che cosa si aspetta ora?

«Nulla di buono. Alle

urne ha vinto l’idea che Israele è uno Stato solo per gli ebrei, ci saranno

altre leggi che seguiranno quella sullo Stato-nazione approvata nei mesi scorsi

e il Paese si adeguerà. La parola democrazia perderà di senso, per un motivo

molto semplice. Non puoi definirti democratico e occupare le terre di un altro

popolo per 52 anni consecutivi. L’Israele di Netanyahu lo fa, e non avrà problemi

a continuare a farlo nel futuro».

Da dove può ripartire il Partito

laburista e con lui la sinistra israeliana?

«Una delle poche cose

buone di queste elezioni è che è chiaro che deve esserci un partito unito per

arabi e israeliani, in cui le parti siano pienamente uguali e che parli per

entrambe. Martedì gli arabi hanno fatto un errore a non votare, perché hanno

reso a Netanyahu la vita più facile. L’unica speranza che la sinistra ha di

ripartire è non abbandonare il 20% della popolazione del Paese che ha voglia di

essere perfettamente integrata nella società: i cittadini arabi israeliani

appunto. Invece sia il Labour che Meretz, come del resto Ganz, li hanno

totalmente ignorati, come se non ci fossero, li hanno umiliati per anni: un

errore costato carissimo a cui hanno tentato di rimediare solo nelle ultime

ore, quando hanno capito cosa stava succedendo. Troppo tardi».

Crede che i palestinesi sarebbero

d’accordo con la prospettiva di un partito unico?

«Ci sono migliaia di

persone che sono pronte a lavorare insieme. Ripartiamo da loro. Se fossi un

palestinese oggi mi sentirei umiliato e spaventato».

Da qualcosa in particolare?

«Da tutto. Netanyahu ha

incoraggiato gli estremisti, li ha infiammati. E il Labour è stato a guardare.

Quelli di destra oggi non dicono che Israele ha perso la sua anima, come io

penso, ma che invece l’ha ritrovata. Perché può contare sull’appoggio

internazionale per riprendersi quelli che considera territori storici:

Gerusalemme, il Golan, domani la Cisgiordania. I piani del governo che verrà su

questi temi saranno i più estremi a cui abbiamo assistito. E non solo su

questo».

Su cos’altro ancora?

«Sull’istruzione ad

esempio. Si dice che il nuovo ministro potrebbe essere Bezalel Smotrich di

Otzma Yediuth, un partito xenofobo e razzista che per anni è stato escluso

dalla vita democratica e che ora ci entra grazie a un accordo voluto da

Netanyahu. Per contrastare tutto questo dovremmo creare un sistema di scuole

umanistico, alternativo: come le scuole religiose fondate in passato dallo Shas

e che negli anni hanno prodotto una classe di persone che incarna l’ideologia

di quel partito e lo vota alle urne. Facciamolo anche noi ma con un sistema

scolastico umanistico, aperto, democratico».

Speranze per il futuro?

«Una sola. I documenti

che hanno portato alla messa in stato di accusa del primo ministro per

corruzione saranno resi pubblici a breve. Spero che nella squadra di Netanyahu

e anche nel suo partito, il Likud, ci siano persone oneste che si rifiuteranno

di avere a che fare con una persona che è a giudizio perché accusata di essere

corrotta e criminale. A quel punto il Likud, che non ama Netanyahu in modo

unanime, potrebbe essere costretto a cambiare leader».